Introduction

Examination and assessment of the genital system is an important part of the veterinary management of dairy cows.

The target on many dairy farms is for cows to achieve a calving to calving interval of 365

days.

days.

To achieve this target the reproductive performance of the cow has to be closely managed. Some consider this calving interval to be an unattainable and possibly undesirable goal in high yielding cows.

On many farms it is only achieved by close monitoring of the cows’ reproductive performance and intervention with strategic hormone therapy.

On many farms it is only achieved by close monitoring of the cows’ reproductive performance and intervention with strategic hormone therapy.

An assessment of herd fertility should involve examination of animals, including any problem animals, as they are presented for routine fertility checks.

It should also involve consideration of the farm husbandry and management.

Information required should include the overall disease profile of the farm, milk yields and both past and present fertility records.

The cow has an average gestation length of 283 days.

The cow has an average gestation length of 283 days.

To achieve a calving interval of 365 days she must conceive again within 82 days (365 - 283 = 82) of her previous calving.

Uterine involution is normally complete and resumption of overt ovarian activity has normally commenced by 40 days after calving.

Conception should ideally occur in the period of 40 to 82 days after calving.

Beef cows are subject to less intense pressures because their milk production has to be sufficient only for their own calf.

Conception should ideally occur in the period of 40 to 82 days after calving.

Beef cows are subject to less intense pressures because their milk production has to be sufficient only for their own calf.

None the less, a calving interval of 365 days is very important to enable the herd to calve at approximately the same time and over a short period each year.

Ashort calving period enables the herd and their calves to be fed and managed as a

group.

group.

Monitoring of the reproductive performance is also important in beef cattle.

Much routine fertility work consists of specific and often limited examinations of the cow’s genital system.

A more detailed and comprehensive examination may be requested and is necessary when a

particularly valuable cow fails to conceive.

Much routine fertility work consists of specific and often limited examinations of the cow’s genital system.

A more detailed and comprehensive examination may be requested and is necessary when a

particularly valuable cow fails to conceive.

In every case it must be remembered that the genital system is just one part of the patient. Unless the patient is in good health and her genital system is functioning normally, conception may not occur.

Whenever the genital system is examined the veterinarian should also assess the general health of the patient and be alert to the possibility that disease involving other body systems may also be present.

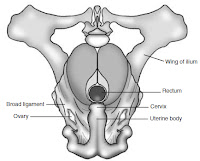

Applied anatomy The anatomy of the female genital system is illustrated in Fig. 10.1. Details of the anatomy of the individual genital organs are given under clinical examination below.

Signalment of the caseThe age of the patient is very important.

Applied anatomy The anatomy of the female genital system is illustrated in Fig. 10.1. Details of the anatomy of the individual genital organs are given under clinical examination below.

Signalment of the caseThe age of the patient is very important.

Maiden heifers have never bred and a small proportion may prove unable to do so.

Some may be freemartins being the twin to a male calf and having the genital tract of an intersex.

Other congenital defects resulting in infertility are rare but none the less must be considered in such a group of animals.

Fertility problems tend to increase with the cow’s parity because the risk of acquired abnormalities increases with the birth of each calf.

Maiden heifers have not yet sustained injuries at calving or experienced problems associated with a retained placenta.

These problems are more frequent in older cows. Such animals are more likely to be exposed to dietary deficiencies which can have an adverse effect on fertility.

History of the case

History of the case

Details of both herd and individual patient history

are of great importance in the recognition and diagnosis

of problems in the female genital system.

History of the herd

The clinician should seek answers to the following questions:

(1) What is the herd size? Has it increased recently?

(2) Are fertility records for the herd available?

On many dairy farms retrospective computerised records are kept.

are of great importance in the recognition and diagnosis

of problems in the female genital system.

History of the herd

The clinician should seek answers to the following questions:

(1) What is the herd size? Has it increased recently?

(2) Are fertility records for the herd available?

On many dairy farms retrospective computerised records are kept.

A number of indices of fertility may be available and consideration of them all is beyond the scope of this book.

Among important indices is the herd submission rate which assesses the vital oestrus detection rate of the herd.

The conception rate and its seasonal change monitored by cumulative sum (Q sum) are also very important.

Poor fertility indices may indicate overall poor performance.

They may also indicate that one section of the herd, for example first calf heifers, is performing badly.

It should also be possible to identify how the herd is performing in the current year compared with previous years.

(3) Herd management – what staff are employed?

Have there been recent changes of staff?

(3) Herd management – what staff are employed?

Have there been recent changes of staff?

What method(s) of oestrus detection are used?

Is a fertility control scheme in place?

Does it include a postnatal check, prebreeding examination and pregnancy diagnosis?

What is the herd policy on cows not achieving herd targets such as being in calf by 82 days?

(4) Feeding and production – what feeding regime is used?

(4) Feeding and production – what feeding regime is used?

Has the diet changed recently?

Are trace element deficiencies known in the area?

Are metabolic profiles taken from cows to assess feeding and identify deficiencies?

Does the farm have a seasonal policy for milk production?

(5) What is the incidence of herd lameness, metabolic disease and mastitis?

(5) What is the incidence of herd lameness, metabolic disease and mastitis?

Have these problems increased recently?

(6) How many cases of abortion occurred during the last year?

(6) How many cases of abortion occurred during the last year?

Was the cause of abortion diagnosed?

Is a vaccination policy in place?

Is a vaccination policy in place?

(7) Is the herd self contained? What was the health

profile of any recently purchased animals?

(8) Is artificial insemination (AI) used? Is DIY AI

used? Are the staff skilled in using AI? Do any

staff members have poor cow AI conception

rates? Is on-farm semen storage satisfactory?

If natural service is used, is the bull known to be

fertile?

History of the cow or heifer

Further questions should be asked or records inspected

to ascertain the following details of the

patient’s history:

(1) The age and parity of the cow.

(2) Has the cow had any previous breeding

problems? What were these? Was treatment

successful?

(3) Details of last calving – date, parturient problems

including dystocia, retention of fetal

membranes.

(4) Dates of observed oestrus since calving – has the

cow cycled regularly? Is she cycling now? Have

her cycles been excessively short or prolonged?

(5) Service details – dates and method of service,

operator, bull or semen used.

(6) Production records of this cow.

(7) Health record of this cow – details of lameness, metabolic disease, mastitis, abortion. Observation of the patient Cows presented for fertility investigation may be confined to a stall or in the parlour.

profile of any recently purchased animals?

(8) Is artificial insemination (AI) used? Is DIY AI

used? Are the staff skilled in using AI? Do any

staff members have poor cow AI conception

rates? Is on-farm semen storage satisfactory?

If natural service is used, is the bull known to be

fertile?

History of the cow or heifer

Further questions should be asked or records inspected

to ascertain the following details of the

patient’s history:

(1) The age and parity of the cow.

(2) Has the cow had any previous breeding

problems? What were these? Was treatment

successful?

(3) Details of last calving – date, parturient problems

including dystocia, retention of fetal

membranes.

(4) Dates of observed oestrus since calving – has the

cow cycled regularly? Is she cycling now? Have

her cycles been excessively short or prolonged?

(5) Service details – dates and method of service,

operator, bull or semen used.

(6) Production records of this cow.

(7) Health record of this cow – details of lameness, metabolic disease, mastitis, abortion. Observation of the patient Cows presented for fertility investigation may be confined to a stall or in the parlour.

Wherever possible the cow should be viewed from all sides without restriction, so that her general health and condition can be assessed.

Certain specific changes may be seen which relate to the patient’s reproductive state.

Many of these are normal physiological changes, but the clinician should look carefully for obvious signs of abnormality which can be investigated further at a later stage.

The condition score of the cow should be estimated and confirmed by palpation of the lumbar and sacral regions when the cow is handled.

Many of these are normal physiological changes, but the clinician should look carefully for obvious signs of abnormality which can be investigated further at a later stage.

The condition score of the cow should be estimated and confirmed by palpation of the lumbar and sacral regions when the cow is handled.

The score (range 1 = very thin to 5 = obese) has an important influence on fertility.

Cows should have a condition score of 3 at calving, 2.5 when served and 2.5 to 3 when dried off.

The cow in oestrus may appear slightly excitable.

The cow in oestrus may appear slightly excitable.

A vaginal discharge of clear tacky mucus (the ‘bulling string’) may be present.

Scuff marks may be seen on her hindquarters and in front of her tuber coxae caused by the feet of other animals mounting her.

Dried saliva from other cows may be seen in similar places. Approximately 48 hours after oestrus the cow may pass a dark red watery vaginal discharge.

Animals suffering from long term cystic ovarian disease may show abnormalities of body shape. Virilism, in which bull-like changes are seen, may occur in animals chronically affected by luteal cysts secreting progesterone.

Dried saliva from other cows may be seen in similar places. Approximately 48 hours after oestrus the cow may pass a dark red watery vaginal discharge.

Animals suffering from long term cystic ovarian disease may show abnormalities of body shape. Virilism, in which bull-like changes are seen, may occur in animals chronically affected by luteal cysts secreting progesterone.

Increased development of the neck muscles may occur and the animal may become aggressive.

Chronic exposure to oestrogens produced by follicular cysts may produce signs of nymphomania.

In addition to displaying frequent signs of oestrus, affected animals may show slackening of the

pelvic ligaments with apparent prominence of the tail head.

Adegree of abdominal distension is anticipated during pregnancy, especially in the last trimester.

Chronic exposure to oestrogens produced by follicular cysts may produce signs of nymphomania.

In addition to displaying frequent signs of oestrus, affected animals may show slackening of the

pelvic ligaments with apparent prominence of the tail head.

Adegree of abdominal distension is anticipated during pregnancy, especially in the last trimester.

Animals carrying twins may show greater than normal abdominal distension.

Pathological abdominal enlargement may be seen in cases of hydrops allantois or hydrops

amnion in which the uterus contains excessive amounts of fluid.

amnion in which the uterus contains excessive amounts of fluid.

The clinical signs of these two conditions are discussed below.

Other causes of abdominal enlargement such as ascites must always be borne in mind and should be detected during the general examination.

In the last few days of pregnancy the sacrosciatic ligaments become relaxed.

The vulva lengthens and appears slightly oedematous. Tail tone appears to be

reduced.

The udder continues to enlarge and may become oedematous.

In some animals the teats leak colostrum.

Mucus from the cervical plug may appear at the vulva.

Body temperature may fall.

Immediately after calving the vulva is still enlarged and a scant bloodstained vaginal discharge is normal for 7 to 10 days.

The pelvic ligaments begin to tighten up again and the perineum returns to its preparturient

state. Afoul brown or red vaginal discharge may in-

In the last few days of pregnancy the sacrosciatic ligaments become relaxed.

The vulva lengthens and appears slightly oedematous. Tail tone appears to be

reduced.

The udder continues to enlarge and may become oedematous.

In some animals the teats leak colostrum.

Mucus from the cervical plug may appear at the vulva.

Body temperature may fall.

Immediately after calving the vulva is still enlarged and a scant bloodstained vaginal discharge is normal for 7 to 10 days.

The pelvic ligaments begin to tighten up again and the perineum returns to its preparturient

state. Afoul brown or red vaginal discharge may in-